Multi Agent RL with Pufferlib

Pico Park is a couch co-op game where you have 2-8 little cats that are forced to coordinate with each other and get through a level. RL agents greedily optimize themselves to maximize their reward, but a game like pico cannot be won by one outstanding player. It forces team work and communication, both of which cannot easily be modeled as a reward.

Humans famously struggle a lot with getting through this game, but let’s see if agents can do a better job.

The Environment

Game Rules

The game involves four agents that have to:

- constantly keep moving to the right to keep up with a sliding screen

- shoot blocks of their respective color to clear a path

- one needs to grab a key to unlock a door

- all four need to exit through that door successfully to complete a level

The game is designed to force spatial coordination because the agents cannot shoot each other, need to move quickly, give each other the space to shoot their blocks, and coordinate on who will get the key.

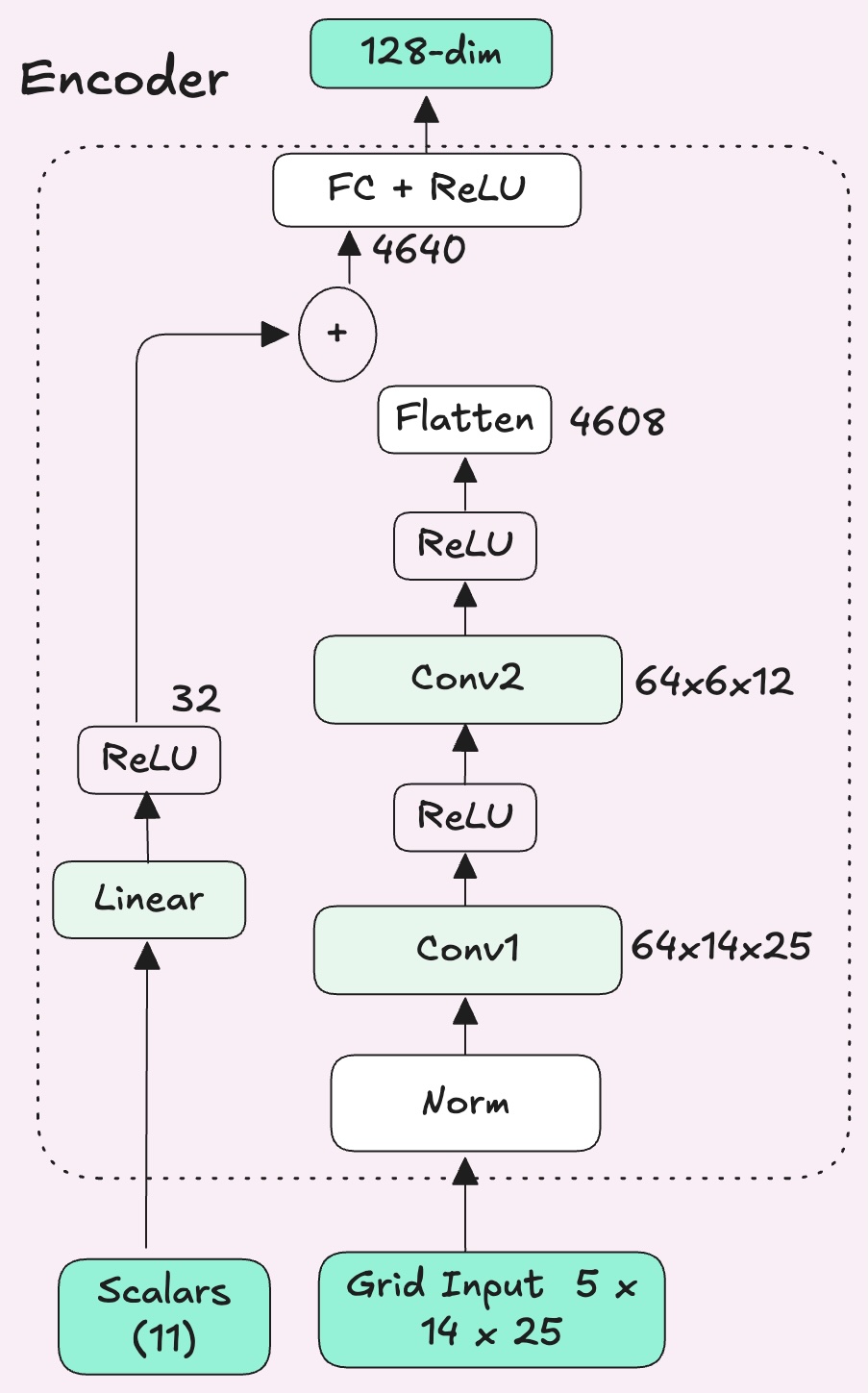

Observations: 5-channel grid of nearby tiles (25×14 viewport centered on the agent), plus an 11-value vector of global state.

Actions: Discrete: move in four directions, shoot, or idle.

The Setup

Team vs. Individual Rewards

The question of whether agents will share rewards for accomplishing tasks or keep independent rewards is important in multi agent RL. I initially started with team based rewards so all agents get rewarded collectively for their actions.

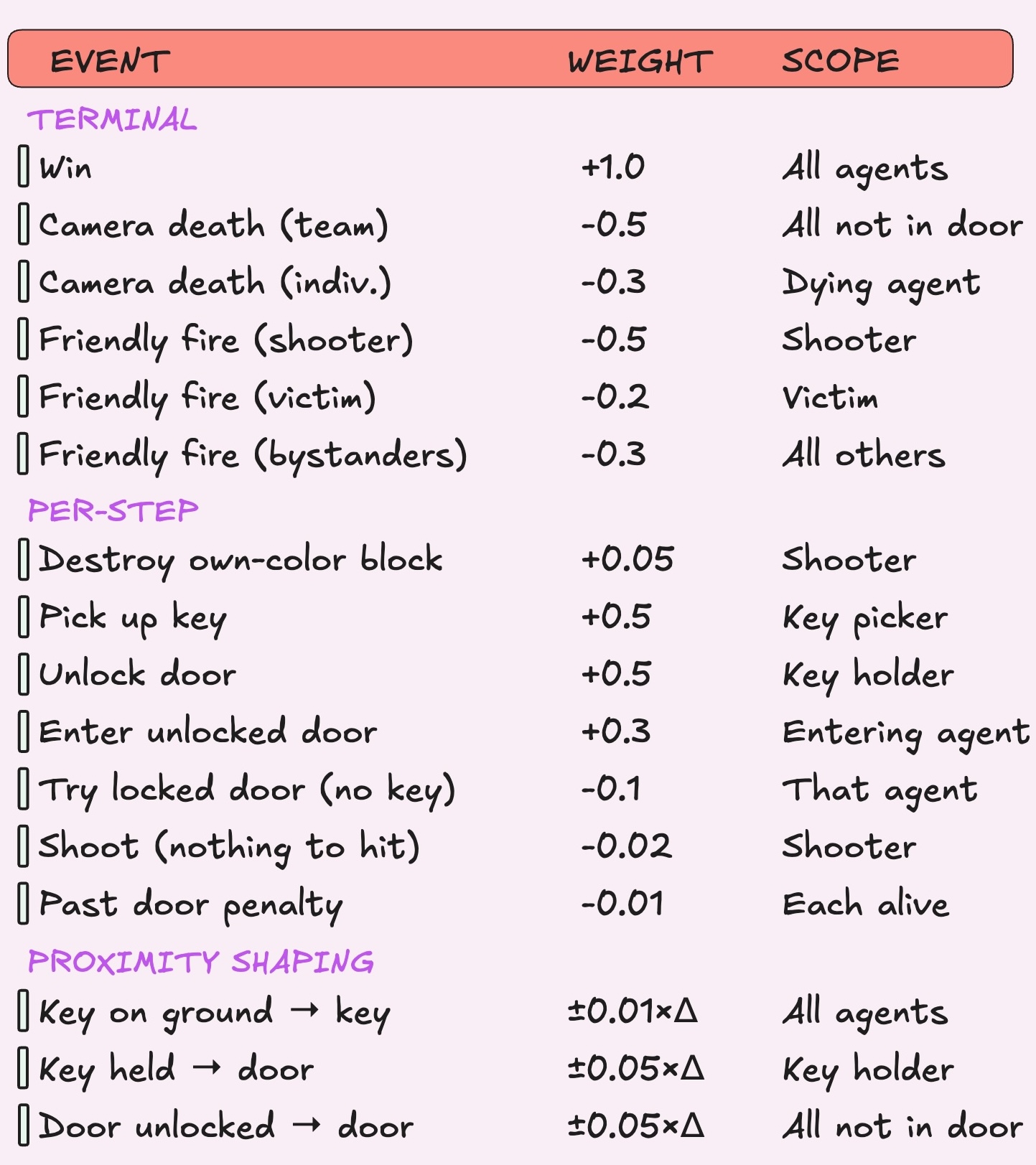

Shared rewards imply that a sense of cooperation is required to solve the problem. While that was true, without individual rewards, the policy doesn't know what action it's actually rewarding. Credit assignment matters and was achieved by adding individual rewards. For example, I added a positive reward when an agent shoots its own block and a negative reward if they kill a teammate.

I started with only a +1.0 win reward and -1.0 death penalty because I was modeling my rewards after simpler environments in Pufferlib like squared.

When a model is first initialized, it starts by randomly flailing its arms around. If this random flailing doesn't create any meaningful signal, the model will never know which direction to grow in. For my environment, making meaningful progress was often a multi-step process. I found that sparse rewards wouldn't give the model enough signal to grow in its initial phase. The model needs a breadcrumb trail to follow.

Encouraging Progress

My first attempt at breadcrumbbing was a keep alive reward. This did help agents learn to move through the map, however they learned to survive instead of win. They would get near the door but not complete the game because they were prioritizing staying in the game to collect the keep alive reward. The ratio between keep-alive and winning wasn't large enough, so staying alive felt more rewarding than pushing for the goal.

I switched to a delta-based proximity reward instead, which rewards distance change to target. The agents get a small reward proportional to how much closer they moved toward the current objective. This reward shifts during different phases: everyone toward the key, then the key-holder toward the door, then everyone toward the door once it's unlocked. Now, the reward followed the next objective rather than just staying alive.

Block Shooting

Rewards can be conceptually correct, but mis-tuning them can make your agents perform worse.

Block shooting was the hardest reward to tune. A small positive reward for destroying your own color block was necessary and without it, the agents never learned to clear paths and couldn't progress. But it introduced other problems.

First, agents started shooting constantly regardless of whether anything was ahead. I added a negative reward for useless shots that don't hit anything, which stopped the spam. But even with targeted shooting, agents got greedy.

They'd stop to farm every block they could find instead of pushing right and agents would die mid-farm because they prioritized the block reward over staying alive. The fix was keeping the block reward small enough that it's never worth dying over.

Addressing Reward Hacking

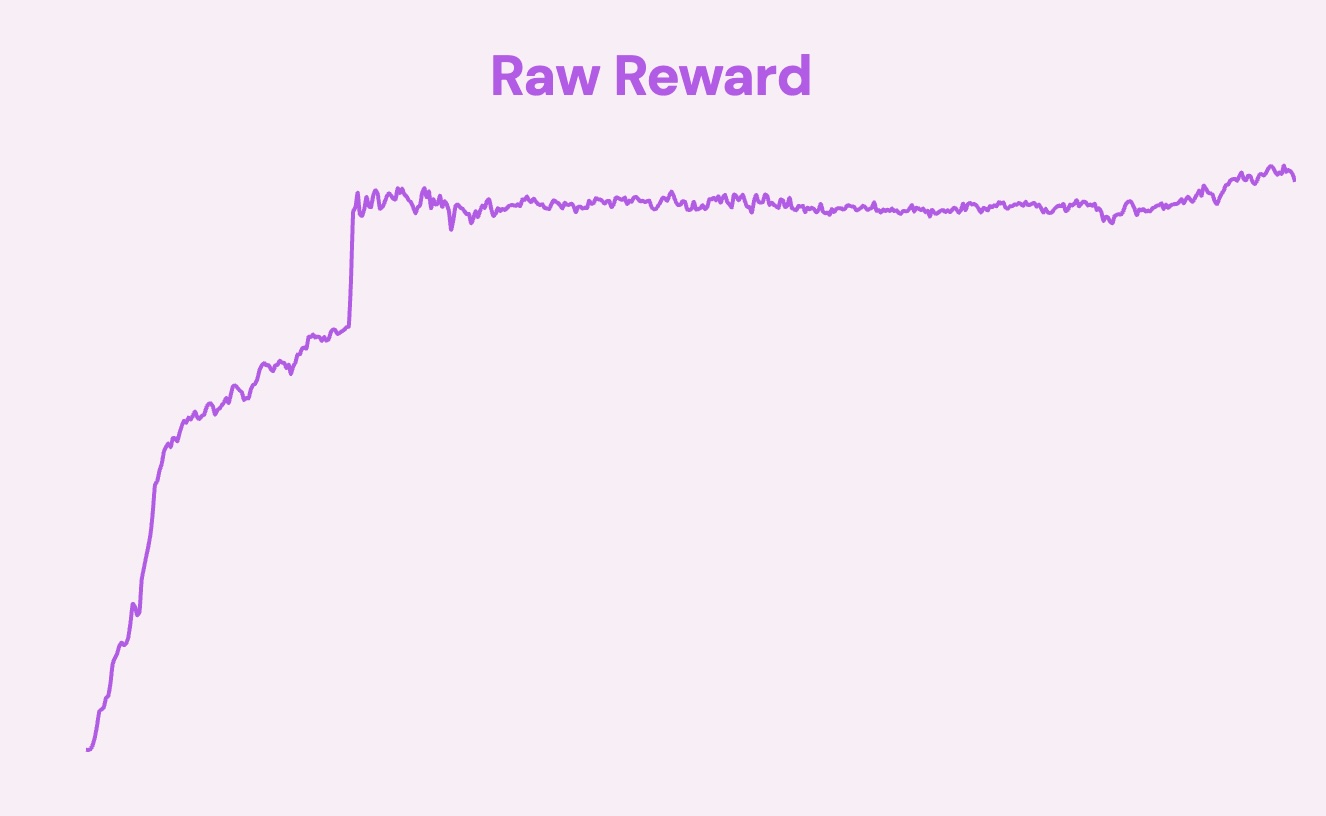

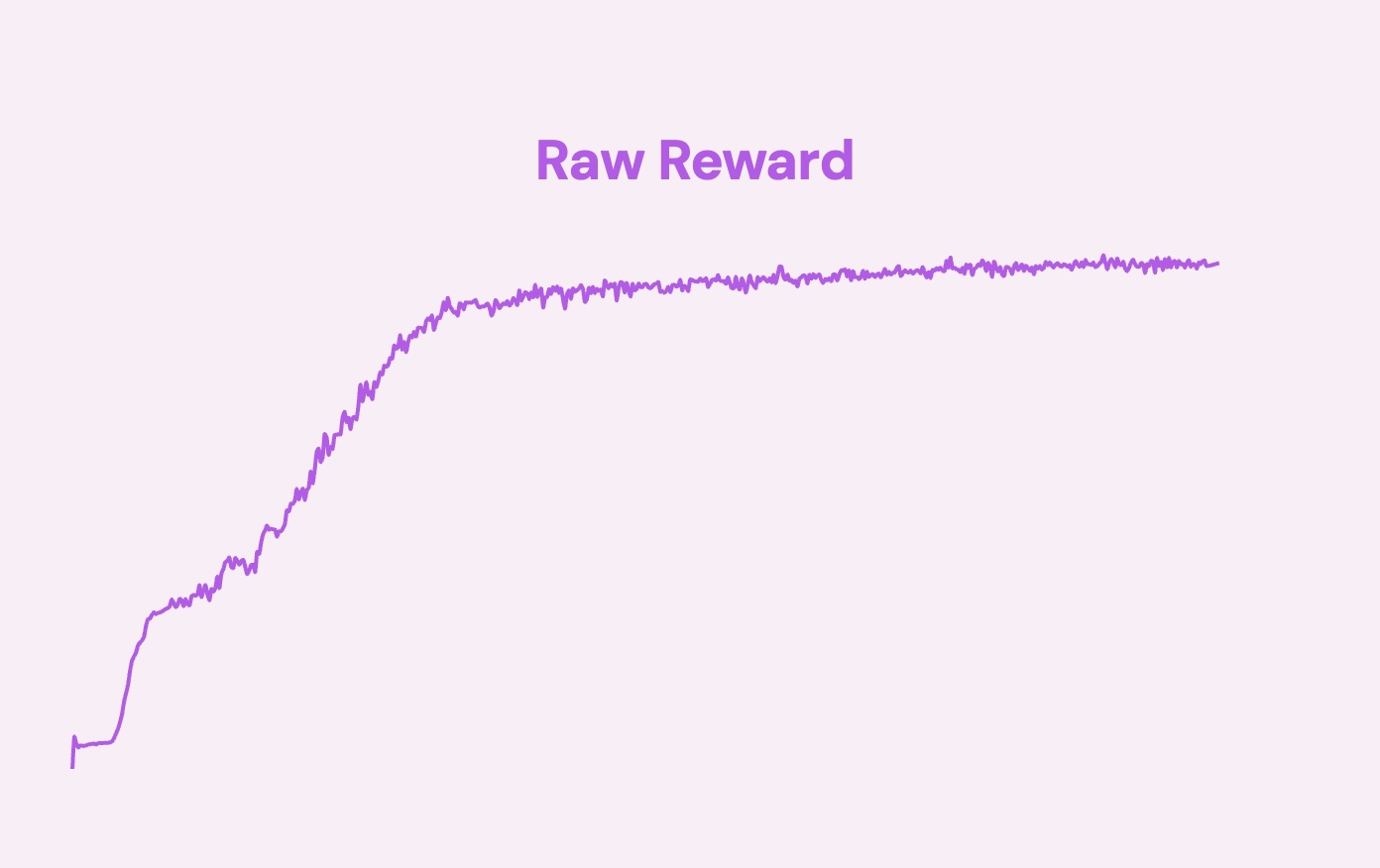

Reward hacking can happen in many ways, one of them is the agent memorizes your environment instead of learning the actual skills needed to solve your environment. Initially, I didn't have enough randomization in each rollout. The environment and the agent's starting positions looked the same.

This gave me really spiky and confusing looking graphs that looked like reward hacking, but in viewing the replays, I couldn't see them breaking any of the rules. The core issue was that the agents weren't learning skills such as coordinating spatially, shooting their own blocks on time, and collecting the key. They were instead memorizing the order in which blocks show up and the positions they had to move to.

Adding randomization made my environment take longer to train but gave me a smoother, more consistent looking graph.

The Agents Learn to Cheat

A stray bullet killing another agent is a very deliberate feature of Pico Park. It forces the agents to learn to make space for each other. When drilling a tunnel through a set of blocks, it forces them to think of how they're going to arrange themselves to make sure each agent has a clear path to shoot the blocks they need to shoot.

The agents however didn't learn any of this, they had found a bug in my environment.

Bullets spawned at the column to the right of the agent, and collision wasn't checked until the next tick after the bullet moved again. Agents were able to get away with positioning themselves directly to the left of an opponent's block or an opponent and shoot through them.

The agents consistently exploited this vulnerability in every rollout and used it to their advantage. They were better at finding bugs in my environment than I was :(

Why an MLP Couldn't See the Map

Throughout my debugging process, I was extremely focused on the reward shaping and thought all my problems solely lied here. However, a major breakthrough was changing my network architecture.

Pico Park is all about communication and coordination. Humans are able to do this in two ways:

- They can talk to each other

- They can just look at what their teammates are trying to do

My agents, however, had to infer their teammates' intentions solely from the positions they'd taken up on the map. The agents' ability to understand its relative position against different objects on the map was really important, and I noticed my network of choice wasn't highlighting these spatial properties enough.

In PPO, the policy network has an encoder (the feature extractor) that compresses the raw observation into an embedding, and then the actor and critic heads read from that to pick actions and estimate value. The encoder determines what the agent actually sees.

PufferLib's default encoder is an MLP which flattens the entire observation into a single vector and pushes it through a single linear layer. Every spatial relationship such as adjacency, direction, distance has to be learned from scratch through weight correlations.

I switched to a CNN that reshapes the flat vector back into what it actually is: a (5, 14, 25) tensor. CNNs slide small filters, across the grid to detect local patterns, such as an agent next to a block or a bullet one tile away. This makes it a natural spatial feature extractor because the structure of the grid is preserved.

The global state, things like whether the agent has the key or where the door is, still goes through a small MLP. I got the idea to separate out my observation space like this from the Moba Pufferlib environment. The two get combined into a single embedding (128 dimensional vector) that captures both spatial relationships and game state.

My Final Rewards

Training Under The Hood

Here's a rundown on how the agents actually learned what to do.

The Core Algorithm

I used PufferLib for training, which implements PPO as it's core algorithm with additional improvements. PPO uses an actor-critic architecture to train a single policy for all 4 agents. The critic learns to estimate value, which is how much total reward it expects from a given state. The actor outputs action logits and picks the actions.

Understanding how the weights need to be updated

There are two parts to producing a model. The architecture you organize your weights in, and the way you update them.

Updating the weights is a multi step process that starts with feedback. What does the model currently do right? What does it do wrong? At a surface level this is easy, you could just look at the rollouts, see where it got a high reward and classify those actions as good, see where there was a low reward and classify those as bad. In practice however, knowing which actions were critical to eventually obtaining a reward ends up being a hard problem. This is the credit assignment problem, which is a key challenge, especially in multi agent reinforcement learning.

Credit Assignment Problem

When an agent does something good, it gets a positive reward. However, the reward often comes later after many actions have happened between the good action and the payoff. The challenge is measuring the influence of each action on the final reward, especially when it may be the result of a long sequence of decisions. To know how much credit to assign to each action, we use advantage estimation.

Advantage Estimation

The advantage is the gap between what actually happened and what the critic predicted. A positive advantage means the action led to a better outcome than expected and a negative one means it was worse. The actor uses these advantages to reinforce good actions and suppress bad ones.

To compute the advantage, we could look at just the immediate reward and the next value estimate, which is low variance but biased because you're trusting the critic's prediction. Or you could look at the full sequence of actual rewards, which is unbiased but noisy. GAE blends these two approaches with a parameter called lambda that controls how far into the future the calculation looks. High lambda relies more on actual rewards, low lambda trusts the critic more.

Do All Actions Matter?

Compute is limited, and we want a dense way of giving the model feedback. Punish for bad, reward for good, but what about when it was just ok? This raises the question about how to track which experience matters most to the model.

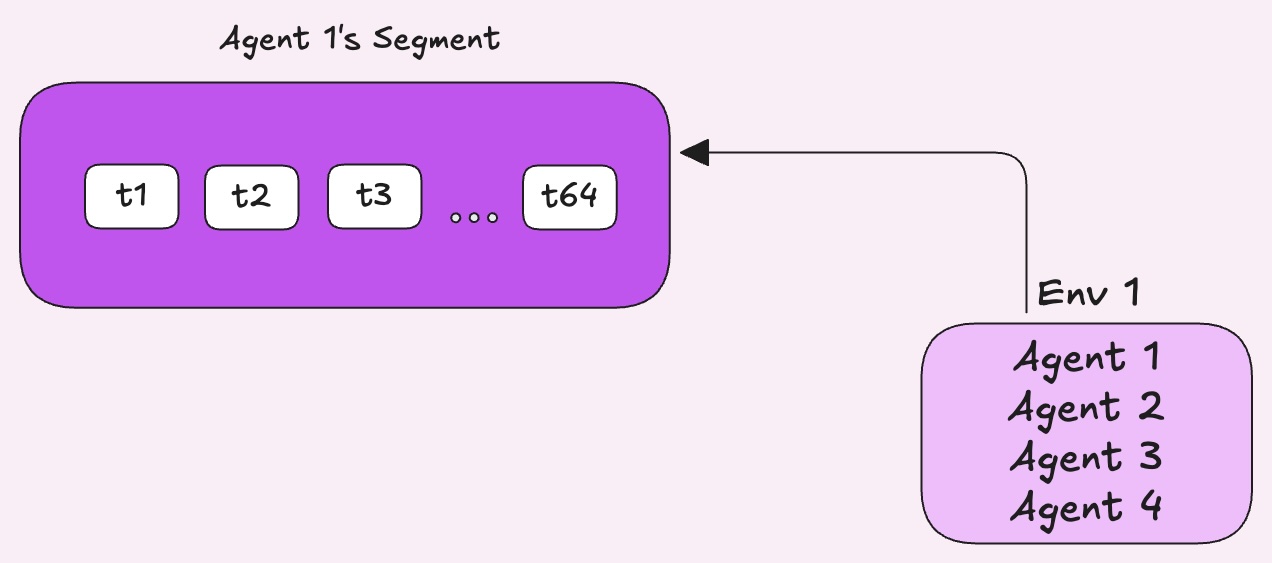

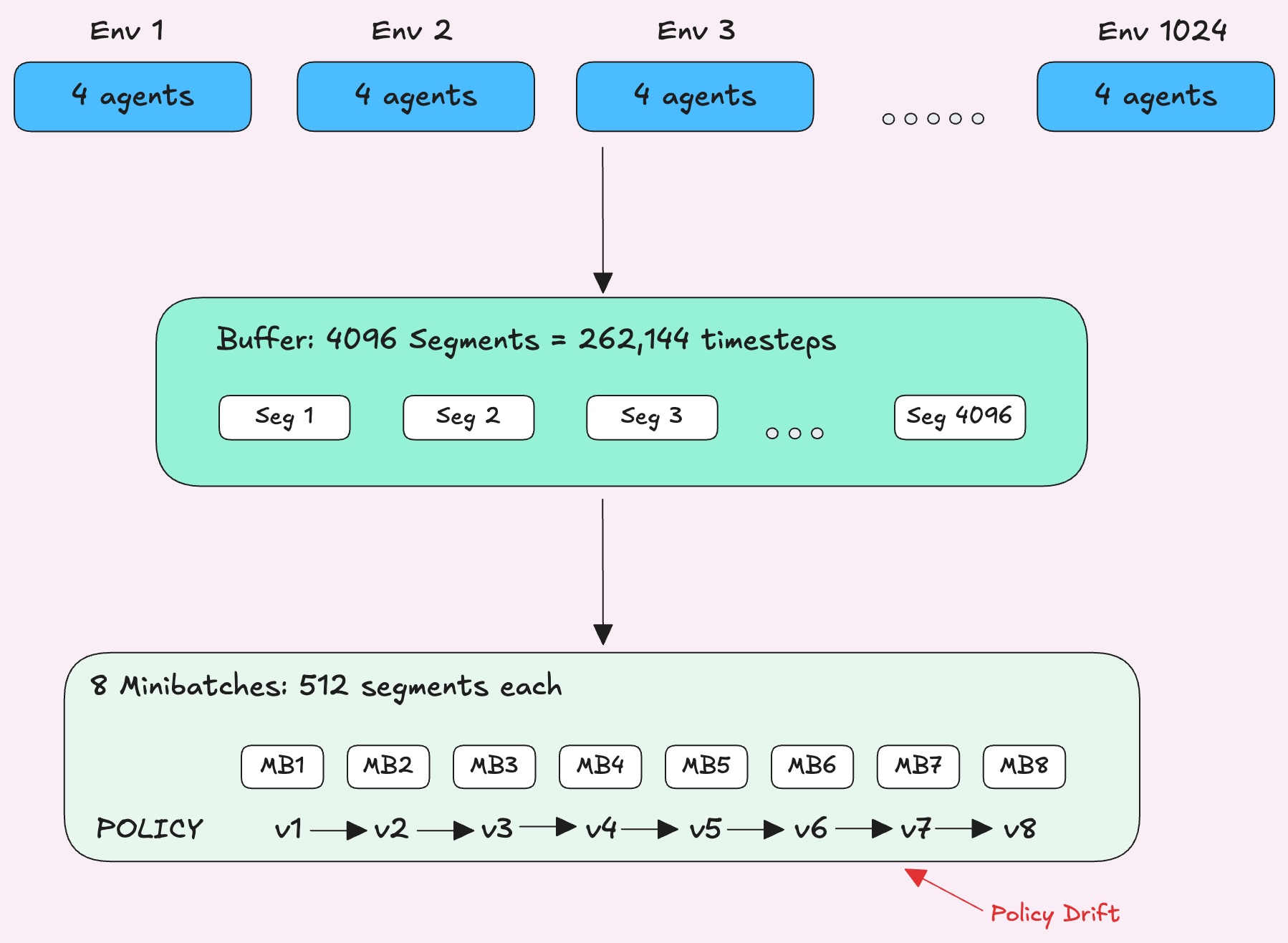

PufferLib looks at the advantage magnitude of each segment, where each segment is 64 consecutive timesteps from a single agent's perspective. Segments where the critic was far off, meaning something surprising happened, get sampled more frequently.

Prioritized Sampling

Segments where the critic was already accurate and nothing interesting happened are less likely to be picked. The idea is to spend more training time on the experience the policy has the most to learn from, adapted from Prioritized Experience Replay.

However, sampling unevenly like this means some segments show up in training more than they naturally would, which can skew the gradient. PufferLib applies a correction weight to each segment's advantage to compensate. This scales down the contribution of over-sampled segments and scales up the under-sampled ones so the overall gradient stays balanced.

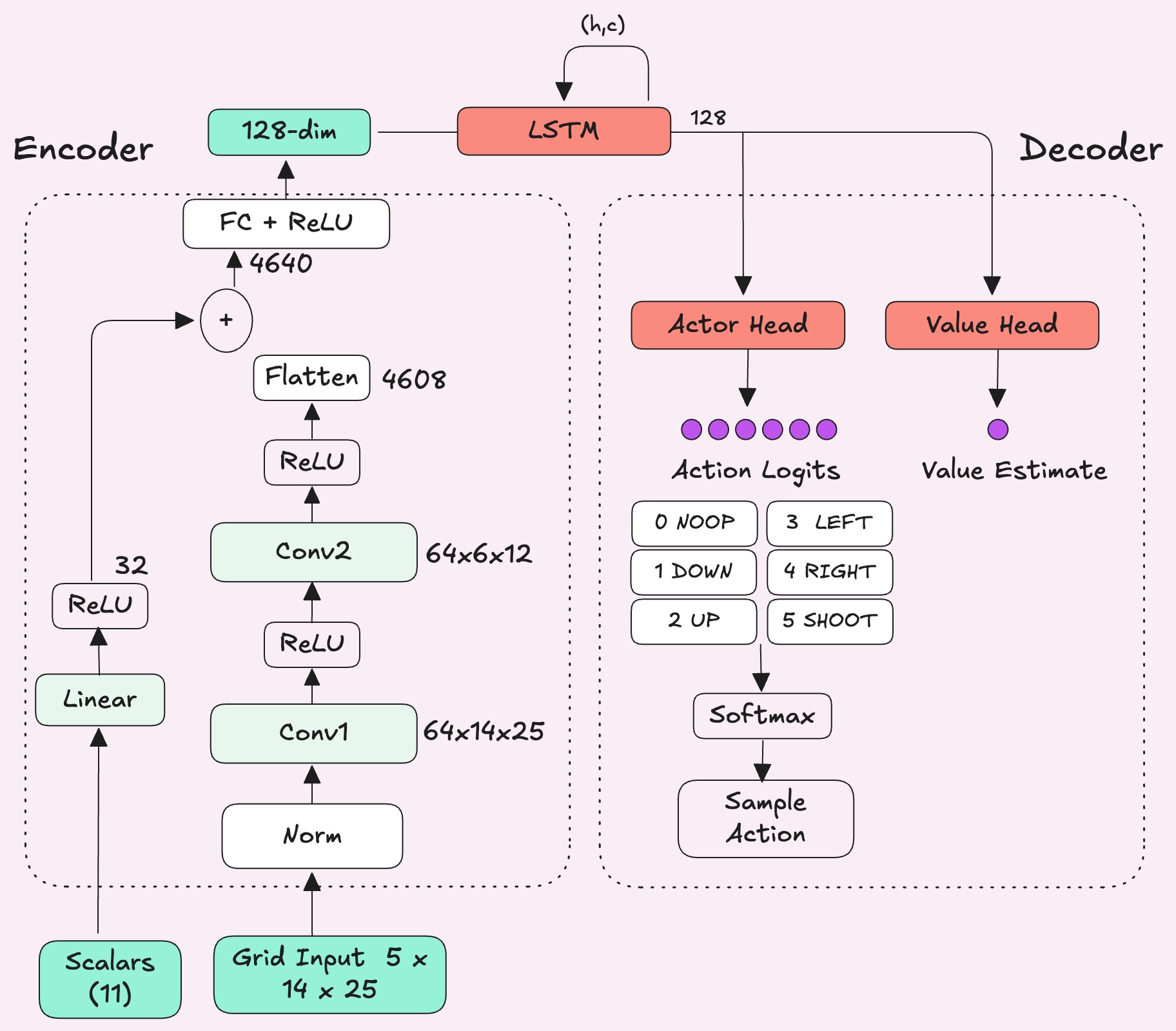

The Architecture

As we saw earlier, the network's encoder is made of 2 components: a CNN for the grid input and an MLP for the global state. The core of the decoder is the two heads: one for the actor and one for the critic.

One thing to note is that to make informed value estimates, the critic needs more information than just the current frame. Is a teammate approaching a block to shoot it, or standing still? Did someone just grab the key? Coordination requires understanding what's been happening over time. It gives the agent a short-term memory so it can make decisions based on the last few seconds of context, not just a single snapshot.

Here's the full architecture of the network:

Pushing Performance Further: How We Use Stale Rollouts

When we collect a batch of experience, the data is on-policy meaning it was generated by the current policy. But training doesn't happen in one shot. The batch gets split into minibatches, and each one updates the policy weights with a gradient step. By the time later minibatches run, the policy has already changed multiple times since the data was collected.

PPO addresses this by tracking a probability ratio for every action that measures how likely the current policy would take that action versus the policy that originally collected it.

This ratio is used directly in the loss function as an importance sampling correction. It multiplies the advantage to scale how much each action influences the policy update. PPO clips this ratio so if the policy has drifted too far from when the data was collected, the update gets capped. This prevents the policy from changing too drastically in any single step.

But this doesn't fix everything. PPO computes advantages once before training and leaves them frozen, so even as the policy drifts, the advantages stay the same.

Fixing Frozen Advantages

Pufferlib addresses this with V-trace, a technique from DeepMind's IMPALA paper. Instead of computing advantages once and leaving them frozen, PufferLib recomputes them before every minibatch using the probability ratio to adjust each advantage based on how relevant that experience still is to the current policy. Actions the new policy has moved away from get their advantages scaled down.

Final Thoughts

I stuck to PPO for this but for anyone looking to recreate this, I'd recommend experimenting with different learning algorithms like GRPO. This was my first intro to training an RL policy and here are some resources that helped me get started:

- Joseph Suarez on Training RL Policies